€100 carbon draws near

Europe's cornerstone climate policy shrugs off the gloom

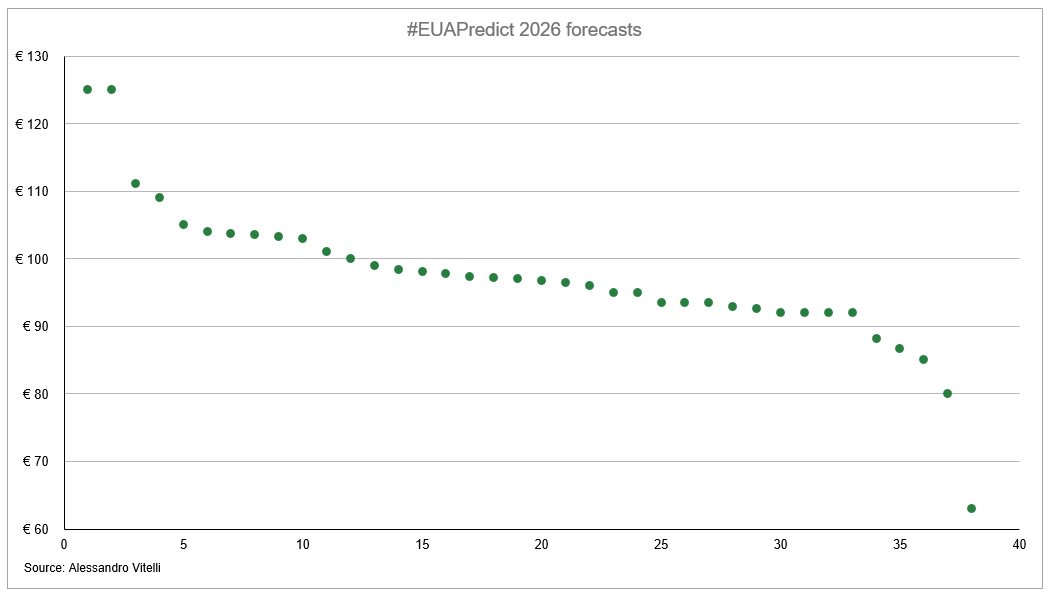

Thank you if you entered the #EUAPredict 2026 competition. The results are now in! The median forecast (based on 38 responses) for the Dec-2026 EUA contract final settlement price was €96.85. The most bullish respondents to #EUAPredict see EUAs ending 2026 at €125, while at the other end of the spectrum, €63 is the most bearish entry received. At the time of writing carbon is trading near €93.

What can we read into this? Well, the mean absolute percentage error across the previous six competitions (based on the median forecast) is 23%. The EU carbon market is inherently volatile and so its no surprise that we get large consensus forecast errors. It's volatility is typically on a par with that of US natural gas; the latter nicknamed the "widow maker" for its ability to hit traders with catastrophic losses (see #EUAPredict 2026: What's your forecast for the EU carbon price in 2026?).

Nevertheless, the median forecast may indicate that people are growing wary of the prospects for further gains. EUA futures have already jumped by more than €20 since the summer and recently breached the €90 mark – the highest level for more than 30 months. The outlook boils down to whether we return to operate in the 2022/early 23 trading environment (broadly €80-€100), or we are in a structurally tighter market, akin to the one experienced in 2021/22 when prices jumped to a whole new paradigm.

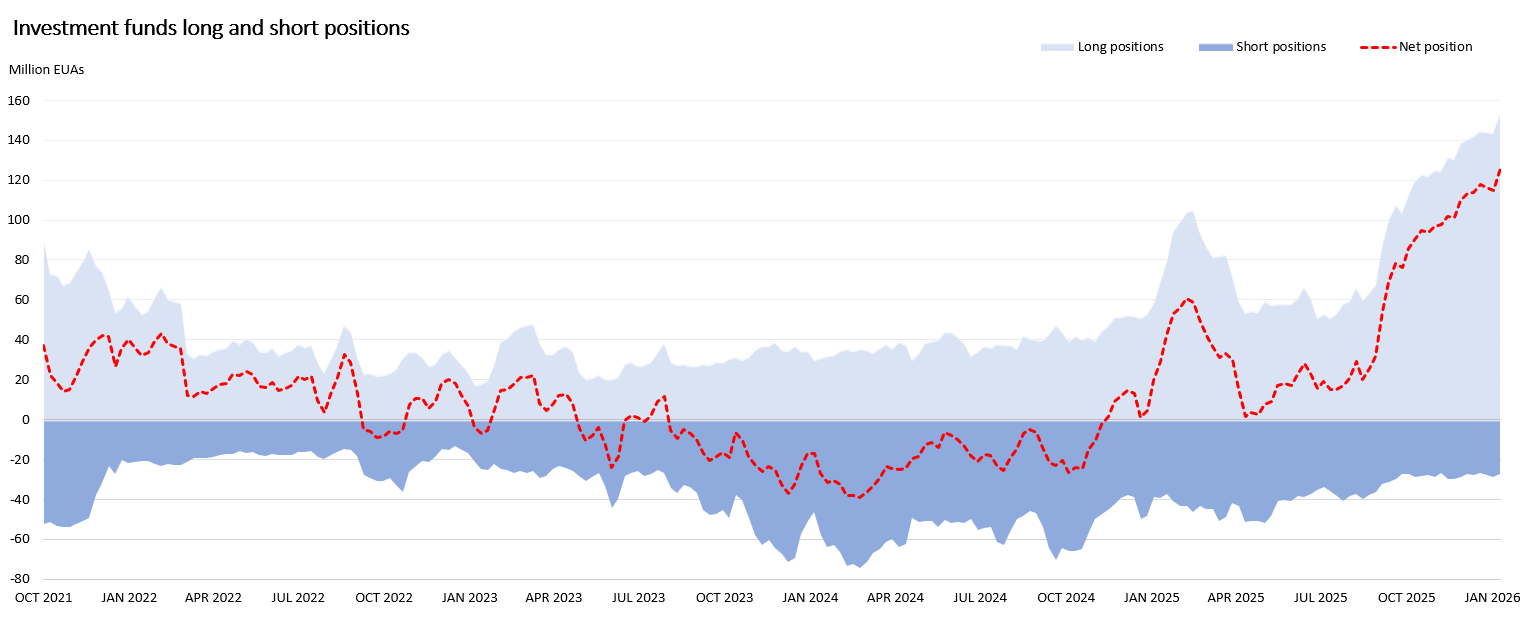

The latest Commitment of Traders (COT) report (w/e 9th January) shows that investment funds have continued to add to their net long position, at 125.6 million EUAs its another record high. As we've seen in recent months, the move higher is the result of new long positions. In contrast, net short positions remain stable at around 28 million EUAs. Funds clearly believe the structural tighter balance story will continue in 2026, and maybe into 2027.

To recap, while the linear reduction factor (LRF) continues to reduce the supply of EUAs, other measures will also tighten the balance, including the end of the RePowerEU frontloading in August, the gradual loss of free allowances to industries covered by CBAM (airlines will no longer receive free allowances altogether), and the maritime sector picking up 100% of their EUA carbon exposure.

The supply of EUAs is naturally highly price inelastic, but even more so in an environment when the balance is tight. It means that there only needs to be a relatively small change in demand and the EUA price moves sharply. Of course the sword of inelastic supply swings both ways. If funds seek to cash in for whatever reason then the market could see a significant drop. Note that similar supply side constraints are building in other markets too (copper for example), and much like EUAs, the funds are positioned heavily long there too.

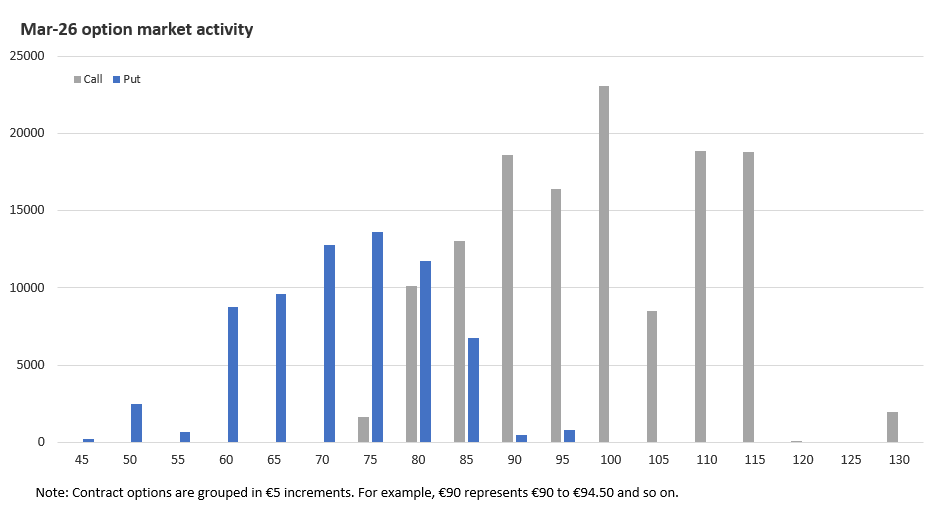

Options market activity for the March 2026 expiry is also hugely bullish. Significant call interest sits above €100 and at 0.52 the put-call ratio is heavily skewed to the bulls. With fund positioning continuing to make fresh records every week calls offer a way of layering in upside optionality without making a direct directional position in the futures market. Overall, the market is signalling that at least in the short-term, EUAs are increasingly likely to push above €100 later this quarter.

Watch the spreads

Up until recently the EU carbon price was typically closely linked to the European natural gas price due to the fuel switching relationship between coal and natural gas. However, since the summer the two have diverged, in a sign perhaps that as coal is forced out of the European power stack, the relationship - the 'clean-dark' spread - no longer holds.

While EUAs have climbed almost 30% to over €90, the last vestiges of the energy crisis have gradually seeped out of the TTF natural gas price. From almost €35 per MWh at the end of July, TTF gradually declined to around €27 per MWh in December, only recovering some losses in early 2026 (but overall its down 17% since the summer).

Lower natural gas prices should be supportive for Europe's energy intensive industries. On the flipside, any further rebound in gas prices (say if LNG supply disappoints, or if there is disruption in the Middle East) would stop any resumption in Europe's industrial activity in its tracks.

In addition, its clear that solar plays a much larger role in the blocs power generation (output rose 20% in 2025 versus 2024). However, the rate of growth in battery energy storage system (BESS) capacity has failed to keep up, limiting the potential for future growth, especially when saturation (low, or even negative intraday power prices) is a recurring risk to developers.

As I note in a recent article, the rate of growth in German BESS capacity - particularly where it is co-located with renewables - is a crucial indicator to watch. If it starts to fall short then it will become progressively more difficult for Germany to add more and more solar power generation. The upshot being an increased reliance on other forms of flex, most likely gas-fired power generation, and higher emissions.

As markets reach critical levels, strange things start to happen and previous linear relationships start to break down. If generation switching economics no longer play the same role anymore, what direction should market participants look towards to see carbon's new 'north star'?

Read the rest of this article with a 30-day free trial*

*and get access to the entire archive!

The MAC curve is steep and opaque

The obvious answer is that the market will transition away from one that solves for the decarbonisation of power generation (fuel switching and incentivising the buildout of renewable energy), to one focused on industrial decarbonisation. In short, that moves us much higher up the marginal abatement cost (MAC) curve.

And so where can we see what that cost curve looks like? Well, again up until quite recently the cost of green hydrogen (H2) was thought to be instrumental, a veritable Swiss Army knife that heavy industries could employ to cut emissions. Back in 2021/22, many analysts thought that green H2 could deliver 20% of the industrial emission reduction required by 2030 under the EU ETS.

In 2020 BNP Paribas looked at a range of potential production costs for green hydrogen and natural gas prices in 2030 and then derived a theoretical value for the carbon price necessary to make green H2 competitive with grey H2, discounting back to 2020. Based on €20 per MWh TTF and €2.5 per kg green H2 a fair value for the EU carbon price in 2020 was ~€60 per tonne CO2 (see Europe's hydrogen economy and what it means for carbon prices).

The cost of grey H2 is highly sensitive to the price of natural gas, and so the recent return to pre-energy crisis levels (€25-€30 per MWh) swings the economics away from green H2 and back towards grey H2. Meanwhile, expectations of a dramatic decline in the price of green H2 in Europe (towards €2 per kg) have failed to materialise as advancements in electrolysis technology and economies of scale have disappointed its proponents.

Fast forward a few years from those heady days of green H2 hopium and its clear that a portfolio of approaches will be needed: clean hydrogen (green, blue, and maybe even white), carbon capture and storage (CCS), electrification, and also carbon dioxide removal (CDR). Rather than there being one tool for the job, it will vary from industry to industry depending on their inherent economic and technological constraints.

Plucking the goose

Jean-Baptiste Colbert, Louis XIV’s finance minister once quipped that “the art of taxation consists in so plucking the goose as to procure the largest quantity of feathers with the least possible amount of hissing.” The EU ETS is no different. A high carbon price increases the incentive to decarbonise, but high carbon prices can have a regressive effect, hampering public support for carbon pricing while also encouraging companies to move to countries with less onerous environmental regulations (see The Carbon Laffer Curve).

The probability of political interference has typically increased as the carbon price approaches €100 per tonne CO2. Back in 2022, as the market toyed with breaking through three figures, Jos Delbeke, a key architect of the EU ETS and Peter Liese, the lead lawmaker steering EU ETS reform through the European Parliament, sought to keep a lid on the market. First, though verbal intervention (roughly targeting a range of €60 to €90), and then secondly via RePowerEU, bringing forward additional EUA supply from future auctions.

With prices approaching €100 once more, is it only a matter of weeks before political intervention resurfaces? Well, you could argue that the introduction of CBAM has begun to mitigate the risk of carbon leakage (i.e., large emitters decamping to other jurisdictions). You could also make the case that with natural gas prices dropping below €30 per MWh Europe's lawmakers will be content to see carbon prices increase to much higher levels than they would have done only a few years ago (see A green and level playing field? The European Commission faces a tortuous task refereeing CBAMs winners and losers).

On the other hand, bear in mind that CBAM means that higher carbon prices will reverberate across the globe, impacting on Europe's relationship with its main trading partners. Meanwhile, the cost of carbon accounts for a much larger proportion of the power price than it did back at the height of the energy crisis, and hence it can have a much larger knock-on impact on inflation. Essentially it means that the EU ETS is a much larger political target now (see In search of carbon alpha).

But perhaps political intervention won't come so quickly this time around. In a statement drawing attention to the price dampening impact of REPowerEU, Liese warned three years ago that market participants should use the opportunity to prepare, not rest on their laurels:

"...we will have to increase our efforts again by the end of the decade. By then, we will be in a position to achieve this because the excuse that there is a shortage of materials and skilled workers will no longer hold true in a few years' time. If you have not invested by then, it's your own fault."

Later, in early 2024, as the carbon price slumped to €60 Liese was moved to state that the bear market presented European industrials with an opportunity, and one that they should make the most of while they still can:

“There is now a phase in which companies can take a deep breath to plan and tackle their investments. The number of certificates will become significantly more scarce from 2027 onwards. And anyone who has not invested or started to invest by then will pay very dearly in the long term.”

The pre-emptive restructuring of the mechanisms underpinning ETS2, and the decision to delay the start of the carbon price by one year, means there is an increasing focus on the forthcoming review of the ETS1 Market Stability Reserve (MSR), scheduled for July (see Softening the blow).

What if carbon pushes through €100? Well, even if no direct intervention is likely during the first half of the year, expect the noise from policymakers and some Member States to get progressively louder as the review process draws near. Peter Liese and others may have warned that higher carbon prices would arrive sooner or later, but that doesn't mean the European Commission will feign deaf ears.