Escaping hells kitchen

Advanced cookstove methodologies offer a promising recipe to slash emissions and cut air pollution

Almost 2.5 billion people, approximately one-third of the global population, cook their meals on open fires or basic stoves, burning wood, agricultural wastes, charcoal, or even animal dung. The smouldering biomass releases harmful pollutants such as small particulate matter that accelerates respiratory and cardiovascular disease, and contributes to around 3.7 million premature deaths each year.

Although the situation has improved in recent years, many lower-income parts of the word remain heavily exposed to indoor air pollution from cooking. The region with the highest rate of exposure is Africa, where 40% of people are exposed to indoor air pollution from solid biomass fuels, followed by Asia on 15-20%.

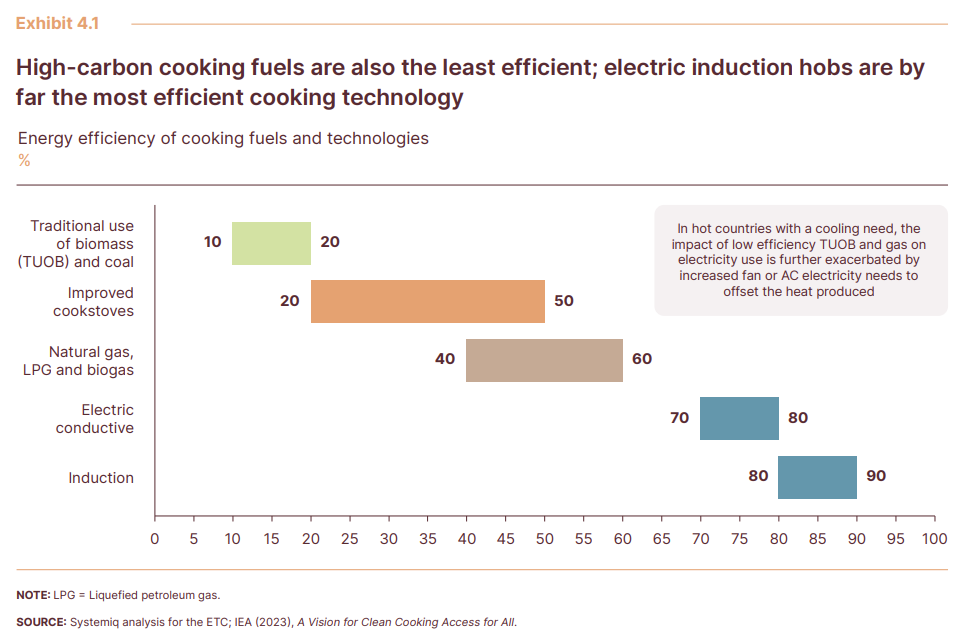

Traditional biomass stoves are extremely inefficient with only 10-20% of primary energy converted to useful heat. More efficient biomass stoves can increase fuel efficiency to around 50%, with the degree to which they reduce emissions dependent on the sustainability of the biomass harvested to fuel the stove - a factor known as the fraction of non-renewable biomass (fNRB).

The next most efficient means of cooking (converting 40-60% to useful energy) are stoves fuelled by biogas or LPG. The latter has the advantage of being easy to transport and store in pressurised cylinders. It also emits around half as much GHG's as the average traditional biomass stove. Biogas stoves offer the highest potential emission savings, but the fuel supply is often unreliable with stoves an expensive upfront cost.

Conductive electric stoves deliver up to 80% efficiency with inductive stoves maxing out at 90%. Aside from the high cost of electric stoves, the main challenge is access to a reliable supply of electricity, and where it is available, the degree to which the grid is powered by low carbon generation. For example, around 75% of the population of Sub-Saharan Africa lack access to electricity, although this is likely to improve as solar panels combined with batteries come down in price.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates that achieving universal clean cooking by 2030 could reduce GHG emissions by 800 Mt CO2e per year, plus an additional 700 Mt CO2e per year due to avoided deforestation. The IEA's estimate excludes black carbon, a short-lived aerosol emitted when burning biomass with a 20-year warming impact up to 4,500 times greater than CO2. As such, clean cooking is likely to make a significant difference in slowing near-term global warming as well as longer-term climate change.

How much does this cost? At the moment, annual investment in clean cooking is estimated to be around $2.5 billion, of which a fraction (~7%) is directed at the region most at need, Sub-Saharan Africa. The IEA thinks that annual investment in clean cooking will need to rise to $8 billion between now and 2030 to achieve universal access. A cumulative investment of around $60 billion, of which almost 80% would be spent on advanced stoves. Working out at ~$40 per tonne CO2, universal clean cooking is one of the most effective carbon abatement opportunities around.

Read the rest of this article with a 30-day free trial*

*and get access to the entire archive!