Could transition credits solve Asia's coal dilemma?

Coal-fired power generation capacity accounts for around 40% of Asia's energy mix, well above the global average of 25%. Although the share has dropped by 10 percentage points since 2010 (in part due to the rapid growth of solar generation capacity), continued investment in new coal-fired power plants (CFPPs) means that coal is likely to remain an important source of electricity in Asia for decades to come.

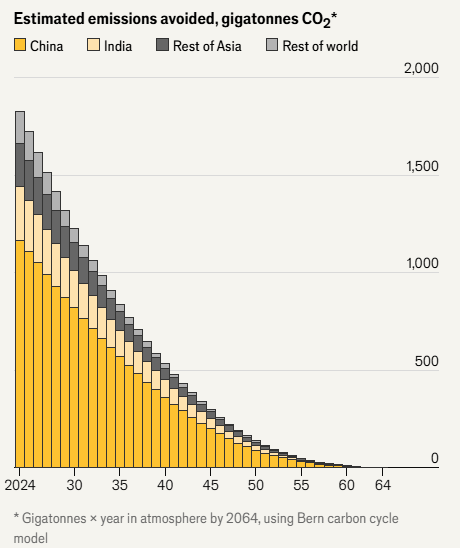

However, Asia's continued reliance on coal means higher emissions. The regions current and planned CFPPs are projected to emit more than 1,600 Gt CO2 cumulatively between now and 2064, according to analysis by The Economist. Their workings takes account of the number of years each CFPP is likely to have left before decommissioning, the share of its generation capacity currently in use, and the emissions expected if it continues to operate at that capacity. The earlier that the CFPPs can be shutdown, the more cumulative emissions can be avoided.

The age composition of a country’s coal fleet determines the financing needed to decommission the assets. In general, it becomes cheaper to retire a coal plant once the initial investment has been recouped (typically up to 20 years). After this point the cost of retiring the asset depends on factors such as system reliability, power supply and demand dynamics, and any power purchase agreements (PPAs) that are in place.

At present almost 80% of Asia's CFPPs are less than 20 years old, according to an analysis of Global Energy Monitor data compiled by Zero Carbon Analytics. If only those CFPPs currently in the pipeline come online then almost one-third (30%) of Asia's plants will be less than 20 years old by 2040. However, if no new plants are built then the share falls to 10% by 2040. Curbing the permitting and construction of new plants is crucial to reducing the cumulative environmental impact. The next best option is to accelerate the decommissioning of those CFPPs currently operating.

But therein lies the catch.

Closing a profitable CFPP before its time typically results in a substantial commercial hit. Its owners are only likely to agree to close it early, if they are ate least compensated for the foregone net present value (NPV) of future cash flows. The cost associated with closing a particular CFPP is likely to vary considerably on a project by project basis, and will depend on factors such as plant age, its thermal efficiency, historical emissions, the operators financial structure, cost of capital, and PPA flexibility, etc.

Governments and financial institutions such as the Asian Development Bank (ADB) have introduced mechanisms that have tried to accelerate the closure of CFPPs, For example, in 2021 the ADB launched the Energy Transition Mechanism (ETM) in partnership with the governments of Indonesia and the Philippines. The ETM pools funds from public and private sources, helping operators of CFPPs to lower their cost of capital, enabling them to pay down equity and debt faster, and hence incentivise the early retirement of CFPPs, while accelerating the deployment of renewable energy.

However, its heavy reliance on concessional capital (i.e., loans and other forms of financing offered on more favourable terms than what is commercially available) has proven insufficient to mobilise the necessary private capital. Only two pilot projects are in the works. Earlier this year Indonesia’s government announced that it would retire the 660MW Cirebon-1 CFPP by 2035, seven years earlier than initially planned. The second project, the 1050MW Pelabuhan Ratu CFPP, is expected to close in 2037.

In its place, an alternative method is starting to gain traction. Transition credits aim to monetise the emissions avoided through the early closure of a coal-fired power plant (CFPP) and its replacement with renewable energy generation. The concept was first proposed in 2023 by GenZero, a climate investment platform founded by the Temasek, the Singapore-based investment fund.

They are not without controversy. As I outlined in Thermal coal's Coasian bargain: Paying coal plants to retire early is a viable route to net zero, compensating owners of CFPP's runs counter to the prevailing narrative that polluters should pay the cost of the negative externality, and that in turn they will be incentivised to stop production, or clean up their act.

"Instead of making the polluter pay the cost of the negative externality, economist Ronald Coase argued that the entities affected by the externality should pay the polluter to stop. For his counterintuitive insight that paying the polluter to stop polluting can actually make everyone better off, Coase received the Nobel Prize in Economics in 1991.

In the example of coal, Coase’s approach involves considering the total net benefit from the early retirement of thermal coal, while at the same time replacing it with renewable energy sources such as wind and solar, and then seeing how this net benefit is split among the various parties involved (e.g. investors, workers, citizens). Coase’s bargain as he termed it suggests that it’s economically optimal for owners of coal mines and coal generation facilities to be compensated to retire their assets early."

Read the rest of this article with a 30-day free trial