Repost: Coming of age

The evolution of carbon credits fits a pattern of financial innovation

Carbon credits representing 98 Mt of CO2 avoided, reduced, or removed were retired during the first half of 2025, according to MSCI Carbon Markets, up 12 Mt of CO2 (13%) from levels two years ago. It's a remarkable turnaround for an industry that has been in the doldrums ever since a sentiment driven boom turned sour in the early 2020's.

Emerging compliance carbon pricing mechanisms, particularly in Asia, are underpinning the revival in corporate use of carbon credits. A trend that is set to accelerate between now and 2030 according to Hannah Hauman, global head of carbon trading at Trafigura:

“Historically, 80% of the market has been voluntary in nature, but what we see changing now very substantially is that flipping where within the next few years, 80% of the demand is actually regulatory based, not voluntary based.”

Indeed, the term 'voluntary' increasingly feels disconnected from both the current realities facing the carbon credit market, and the emerging consensus as to how its future is likely to evolve. The market is underpinned by verification: research, monitoring, reporting, auditing, and engagement. Rather than using the term 'voluntary', more and more stakeholders are coming round to the view that 'verified' carbon market makes a lot more sense.

Not all carbon credits are equal of course, based as they are on individual projects, each with their own unique challenges and risks to delivery. The gradual harmonisation of methodologies, labelling, and ratings towards higher standards should now move the sector towards something that resembles todays physical commodity markets. As participants in the latter know all too well, trust is the bedrock to any well-functioning market - the carbon market is no different.

In the article below, first published in December last year, I explain why the evolution of carbon credits fits a pattern of financial innovation mirrored by other asset classes such as the expansion of the commodity futures derivative market. The latter boosted liquidity, led to the securitisation of commodities, and enabled buyers and sellers to better manage their risk. The same could now be on the horizon for carbon.

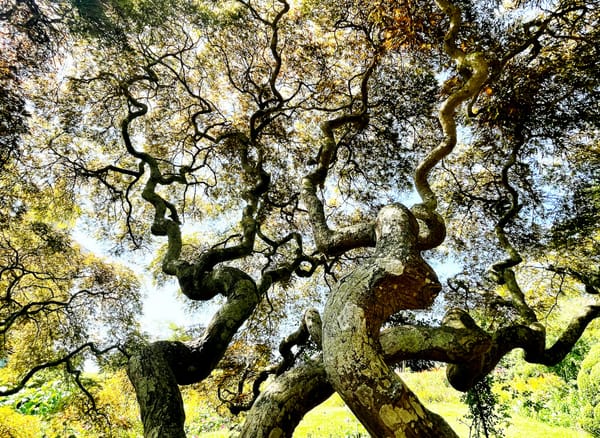

The first carbon project dates back to the late 1980’s.

Concerned about the climate impact of the coal plants his company was developing, the CEO of Applied Energy Services (AES) Roger Sant, sought the advice of the World Resource Institute (WRI). That conversation gave birth to the first avoided emissions carbon credit project. AES agreed to fund the planting of trees and the protection of forest in Guatemala, in return for offsetting the emissions of its coal plants in the United States.

It wasn’t for another decade that governments first entertained the idea that carbon credits could also be the most economical way of meeting national climate targets. Negotiators working on the Kyoto Protocol developed a scheme known as the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM), aping the early innovation employed by AES and its successors.

Barclays was one of the first financial institutions to secure a foothold with which to benefit from the growth in carbon markets. The bank launched its carbon trading business in 2004, prior to the ratification of the Kyoto Protocol (February 2005), and before the EU ETS began operating (January 2005). Other banks were quick to follow, attracted by the potential opportunities in financing, origination, and market making.

The first carbon panic

Global financial turbulence, coupled with political uncertainty, punctured the banks enthusiasm for the carbon trading business. First, EU carbon prices began to fall in May 2008, coinciding with the start of the Great Financial Crisis (GFC). After peaking near €30 per tonne, carbon prices declined to below €10 per tonne by mid-January 2009 as the market anticipated a deep recession would cut emissions, resulting in lower demand for EUAs.

The EU carbon price rebounded somewhat during 2010 and into early 2011, but it wasn’t long before it was under pressure once again as the European sovereign debt crisis erupted. From a high of almost €17 per tonne in May 2011, the carbon price fell to less than €5 per tonne by mid-2013 as carbon market participants feared an increase in the allowance surplus as economies suffering under the weight of austerity would inevitably slow.

The pressure wrought by the GFC and the subsequent Euro debt crisis were the main factors behind the collapse in the EU carbon price, but two other factors made the situation worse. First, the break down in negotiations at COP15, held in Copenhagen at the end of 2009, added to the poor sentiment in the carbon market.

Second, there was a enormous influx of cheap carbon credits (amounting to ~1.2 Gt of CO2) from the CDM and the UN’s Joint Implementation (JI) programme during the period 2008-2014. Japan’s retreat from its climate targets following the Fukushima nuclear accident added to the surplus. The price of certified emission reduction credits issued under the CDM gradually fell from €25 per tonne of CO2 in 2008 to €10 per tonne of CO2 in 2011 before crashing to €0.50 per tonne of CO2 in 2012. Unlike the situation now, EU ETS obligated entities were able to meet their compliance needs through international carbon credits.

Many financial market participants had seen enough and started to scale down their carbon trading operations or merged them with their power and gas trading operations (e.g., JP Morgan and Morgan Stanley), or simply got out of the business altogether (e.g., Barclays, Deutsche Bank and UBS).

In addition to the political and structural risks present in the nascent cap-and-trade market, new banking regulations and compliance requirements, introduced in the wake of the GFC, curbed banks ability to trade. Overall, the number of workers employed on the carbon desks of London’s financial centre fell from close to 1,000 in early 2010 to ~200 by the end of 2013.

“To da Moon”

It wasn’t until 2023, after a decade-long hiatus, that Barclays sought to rebuild its carbon trading desk. The bank’s outlook for the VCM has been particularly bullish, anticipating the opportunity for exponential growth as net zero targets draw near.

Barclays published a report at the time in which they predicted that the VCM would hit a “tipping point” in the near future, enabling it to grow from $0.5 billion currently, to $250 billion by 2030, before reaching $1.5 trillion by 2050. Other institutions were also bullish, albeit to a lesser extent, calling for it to be a mere $50-$100 billion market by 2030 (see Is the VCM a trillion dollar business opportunity?).

Nevertheless, 2023 was arguably the peak for the VCM.

Read the rest of this article with a 30-day free trial*

*and get access to the entire archive!