Nature for sale

Biodiversity credits and offsets are a distraction from the real problem

"While the costs cannot be precisely calculated, treating nature’s economic value as zero is tantamount to considering it as a 'free good'. This sustains a huge flaw in the global financial system." - Hank Paulson, founder and chairman of the Paulson Institute

The Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF), adopted at the UN Convention on Biological and Diversity COP15 in 2022, set a target that by 2030, at least 30% of degraded terrestrial, inland water, and marine and coastal ecosystems would become protected areas. Unfortunately, progress has largely stalled with just 17.6% of the land and 8.4% of the ocean estimated to be under effective restoration - well short of the so-called 30x30 target.

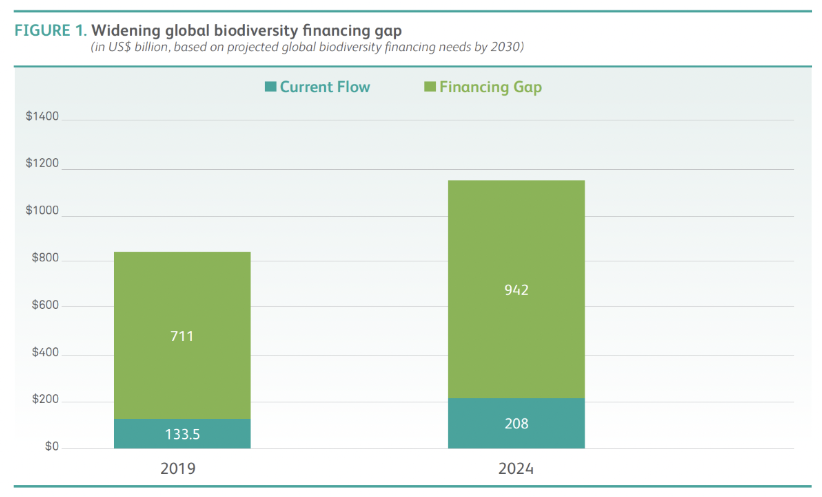

The global biodiversity financing gap is defined as the projected annual funding deficit required by 2030 to sustainably manage biodiversity and maintain the integrity of ecosystems, and in turn help achieve the GBF's target. The gap is estimated to have increased from $711 billion per year in 2020 to $942 billion per year in 2024, according to the interim 2025 Financing Nature report published by the Paulson Institute, equivalent to 0.8% of global GDP in 2024.

The 2020 Financing Nature report by the Paulson Institute identified the most promising mechanisms to close the biodiversity financing gap, split into two categories: those that reduce harm to biodiversity, and those that generate funding to protect or restore biodiversity. Of the mechanisms that could reduce the overall biodiversity funding gap, the reform of harmful subsidies was identified as the single most important measure.

Governments often subsidise the production of agriculture, forestry, and fishing (AFF) to reduce reliance on imports, ensure access to export markets, and protect jobs. By artificially lowering the cost of production subsidies tend to promote monoculture, and incentivise the excessive use of fertilisers and pesticides. Although they lead to an increase in production, subsidies tend to result in an increase in deforestation and biodiversity loss.

The GBF set a goal of reducing harmful subsidies by $500 billion annually by 2030. Alas, the problem has got bigger, not smaller, adding to the growing biodiversity funding gap. Government subsidies on AFF are estimated to have risen by more than 50% over the past five years to $840 billion in 2024 (see Fuelling controversy: Fossil fuel subsidies act like a negative carbon price).

On the other side of the financing gap, funding dedicated to protecting or restoring biodiversity has increased by more than half since 2020, but only to $208 billion per year. In order to close the global biodiversity financing gap by 2030, funding will need to rise five-fold in a similar time frame.

The 2020 Financing Nature report singled out biodiversity offsets as potentially the most important mechanism for increasing capital flows into biodiversity conservation. The Paulson Institute projected that funding via this mechanism would increase from $6-9 billion per year in 2019 to ~$165 billion by 2030.

Note the term 'biodiversity offsets'. The GBF obliges its 196 state signatories to mobilise and leverage financing through “innovative schemes such as…biodiversity offsets and credits”. I'll come to what offsets means in this context in a minute, but for now lets narrow the term to 'biodiversity credits'.

Read the rest of this article with a 30-day free trial*

*and get access to the entire archive!