A uniform global carbon price is unworkable, and unnecessary

Welcome to Carbon Risk — helping investors navigate 'The Currency of Decarbonisation'! 🏭

If you haven’t already subscribed please click on the link below, or try a 7-day free trial giving you full access. By subscribing you’ll join more than 4,000 people who already read Carbon Risk. Check out what other subscribers are saying.

You can also follow on LinkedIn and Bluesky. The Carbon Risk referral program means you get rewarded for sharing the articles. Once you’ve read this article be sure to check out the table of contents [Start here].

Thanks for reading Carbon Risk and sharing my work! 🔥

Estimated reading time ~ 12 mins

The economist William Nordhaus suggested that the optimal strategy to combat climate change is a uniform global price on carbon:

“The most efficient strategy for slowing or preventing climate change is to impose a universal and internationally harmonized carbon tax levied on the carbon content of fossil fuels.”

The argument for a global price centres on its role as a collective commitment tool, incentivising global participation and cooperation. In facing the same carbon price constraint, so the argument goes, countries would also allocate resources more efficiently.

Capital would more easily be directed at the resources and technology required to decarbonise, in turn reducing the overall global cost of meeting net zero. The prospect of carbon leakage would also be reduced in a world where it was more difficult to undercut your rivals.

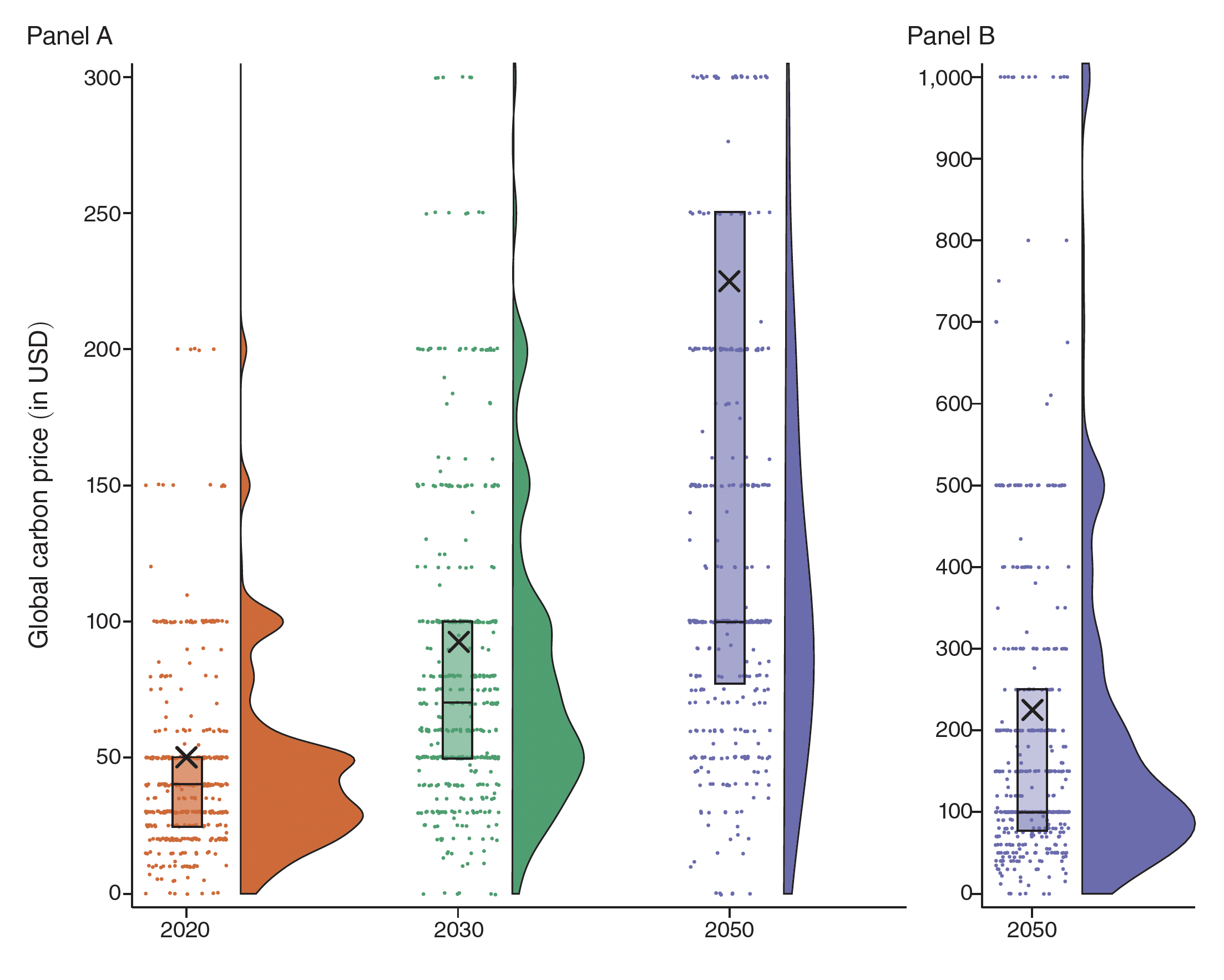

A recent survey of carbon pricing academics asked them to choose a uniform global carbon price, assuming that a “world government” exists and seeks to “maximise the well-being of all present and future people.” Their median response was ~$75 per tonne of CO2 in 2030, rising to $100 per tonne of CO2 in 2050. This broadly tallies with the 2017 High-Level Commission on Carbon Prices (HLCCP), which concluded that carbon prices needed to reach $50-100 per tonne CO2e by 2030, in order to limit global temperature rises to well below 2ºC.1

In reality, a uniform global carbon price is unlikely to be workable. Before we get to some of the reasons why, lets first check in on the status of carbon pricing across the globe to see how far away we are from what the experts suggest.

Note that this isn’t just some academic exercise. It’s going to have real world consequences as exporters of carbon intensive raw materials seek to negate the impact of the EU’s CBAM, or otherwise go to the World Trade Organisation (WTO) arguing their case for a better deal with the EU.

Remember, the CBAM is only payable if the production country-of-origin does not have a comparable carbon price as the EU’s. This effectively pushes countries towards implementing a carbon price at a similar level to Europe. While this helps to coordinate global climate policy and discourage free-riders, it does create inequality (see here and here).

Direct carbon pricing

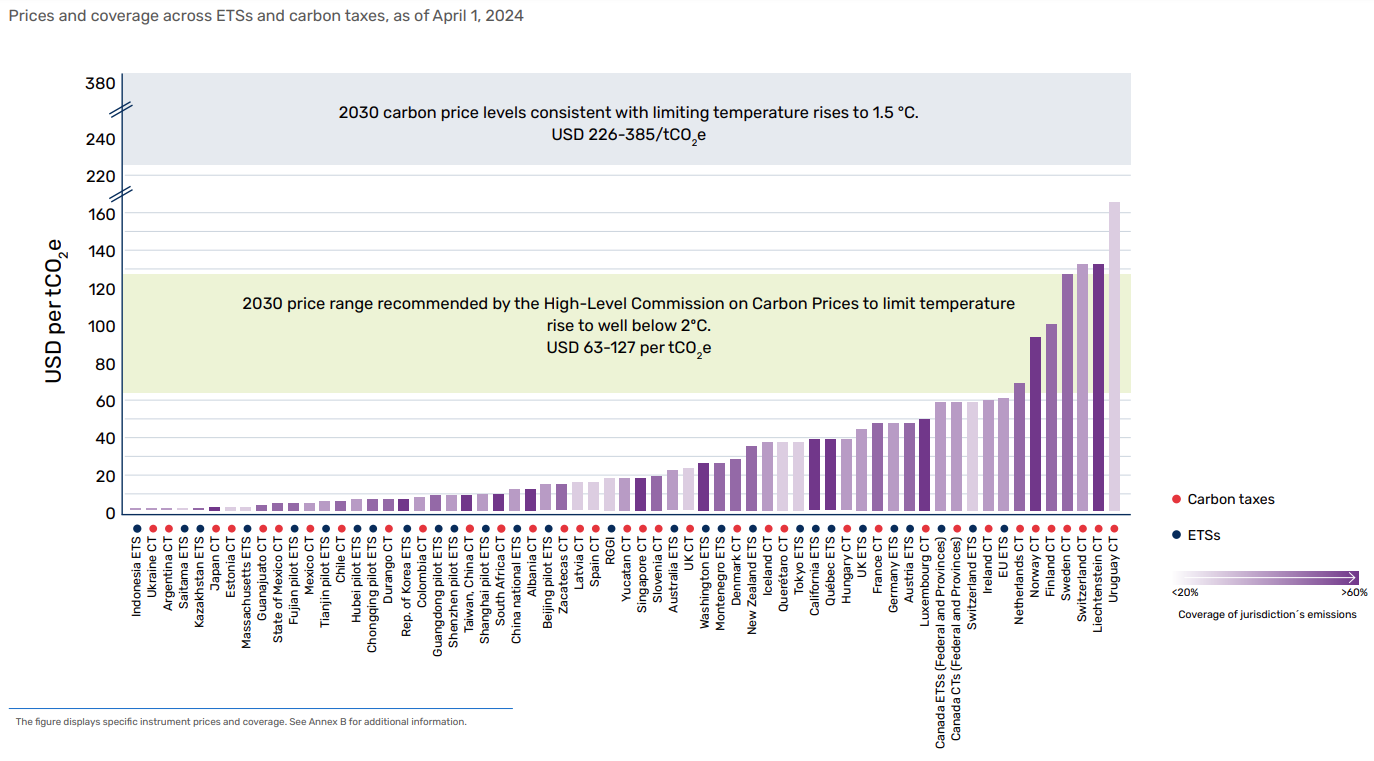

Almost one-quarter (24%) of global carbon emissions are covered by an emissions trading scheme (ETS) or a carbon tax, according to the latest estimates from the World Bank. Approximately 18% of emissions are covered by an ETS, carbon taxes cover 5.5%, while 0.5% is covered by both an ETS and carbon taxes. Although many emerging economies are looking to introduce or expand the role played by carbon taxes and ETS (e.g., Brazil, China, Turkey, and Indonesia), it is very unlikely that carbon pricing will cover more than 40% of global emissions by 2030 (see It's the carbon price, stupid!).

Only seven carbon pricing instruments, covering less than 1% of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, reached price levels at or above the inflation-adjusted minimum level of $63 (€60) per tonne CO2e in 2024 suggested by the HLCCP. Incidentally, the ETS with the highest price represented in the chart below - the EU ETS - failed to meet even this minimum level, at least in April 2024 when the snapshot of prices for the chart below was taken. Many European countries also have a separate carbon tax - some overlap with the ETS, but most do not - but even these tend to be in the $20-$60 per tonne range.

Emerging economies are at the extreme edges of the carbon price chart. At $167 per tonne of CO2e, Uruguay has the highest carbon tax in the world, albeit it only covers 5-10% of its emissions. With the exception of the South American nation, the next emerging economy on the list is Mexico, where the city of Queretaro has a carbon tax of $37 per tonne of CO2e, 22nd in the rankings of carbon price levels. Of the other emerging economies represented in the chart below, few if any have a carbon price above $10 per tonne of CO2e.

The Effective Carbon Rate (ECR)

Most analysts stop there and only focus on direct carbon pricing policies such as ETS and carbon taxes. But to end here and just compare countries based on their direct carbon pricing would be a mistake.