A chaotic patchwork of inconsistent incentives

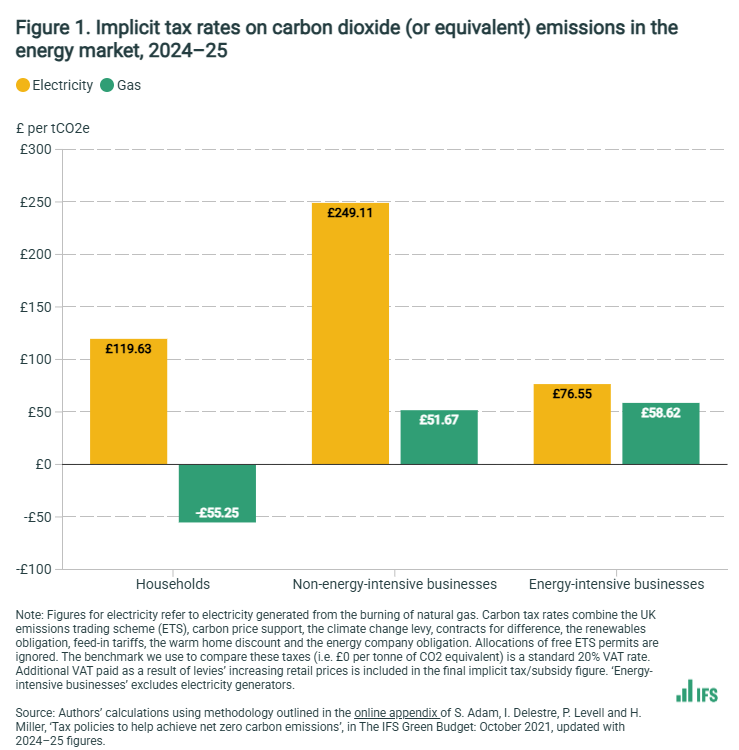

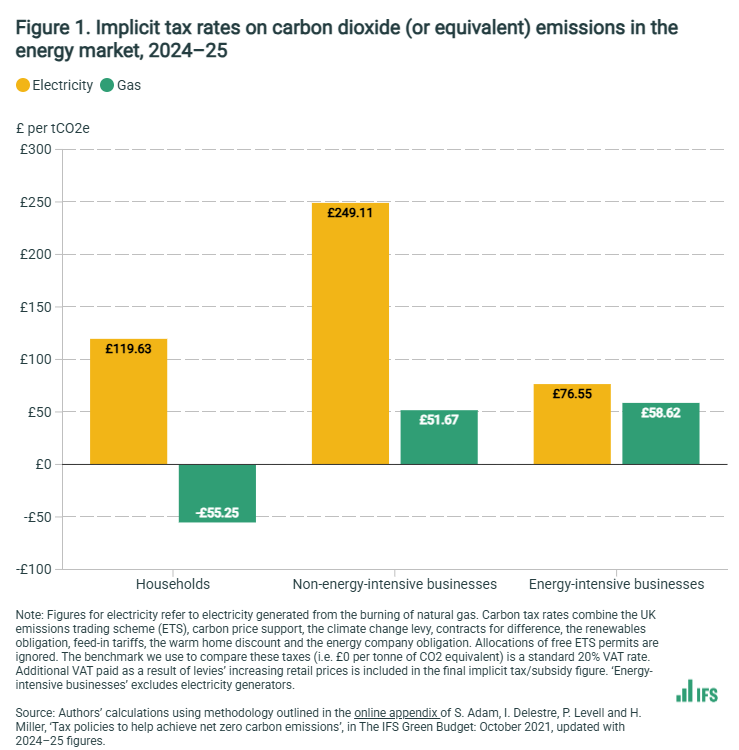

The UK is a carbon pricing pioneer, but it's system of taxes and subsidies makes it more expensive to reach net zero

The UK is a carbon pricing pioneer, but it's system of taxes and subsidies makes it more expensive to reach net zero

For Europe's most influential lobby group, carbon pricing is a delicate balancing act

Korean carbon price jumps 50% as government gets serious about climate, but AI clean energy conundrum awaits

Retracement, evolution, or revolution?

Industry compensation for indirect carbon costs must be conditional